Idea vs. Expression: Where is the line in video games?

Since the creation of the first ever multi-computer played video game in 1961, called “Spacewar”, the industry has evolved towards a high-tech sphere with the use of Artificial Intelligence, Virtual Reality and Blockchain technologies. However, a question still remains open where the line is drawn between copying of the idea (not protected by the copyright) and the copying of its expression (protected by the copyright).

As the most professional Nokia 3310 Snake players at Axon Partners, we analyzed foreign jurisdictions’ case law in order to find an answer to that question.

A video game in the IP context

According to the Cambridge dictionary, a video game is “a game in which the player controls moving pictures on a screen by pressing buttons.” According to Axon Partners’ definition, a video game is “many IP objects, merged into one IP product, which does not let us sleep at night.” At first sight, everything is pretty simple. However, this is only at first sight.

Generally speaking, a video game and its elements can have copyright, trademark, patent and even trade secret protection, depending on the jurisdiction and circumstances. In some states, video games have a distributive classification (USA, Japan, India, Germany), in some, they are considered as computer programs (Canada, China, Israel), and in very few as audiovisual elements (South Korea).

It is unlikely that you will find a case where parties were going to court due to direct copying of a game or violation of rights by stealing the source code, audio or pictures of the game. Ok, maybe such cases exist, however, is it interesting for someone to read them? At the same time, the copying of the game, as a single object of IP, copying of the gameplay or general industry practice is a different story. Let us look for something interesting in case law with such focus.

Idea vs. Expression

We are too young to discuss “Spacewars” (1961) and we are too old to discuss “Fortnite: Battle Royale” (2017), therefore let’s discuss something that everyone can understand – Shariki (1994), Bejeweled (2001) and Candy Crush Saga (2012). If you have never played these games, then you have at least seen someone playing them in the subway. The idea behind each of these games is that, as a player, you need to swap one piece of the puzzle with a neighboring piece to form a horizontal or vertical chain of three same pieces of puzzles of the same color. Then they get demolished, and you receive points.

From left to right gameplay of: Candy Crush Saga (2012), Bejeweled (2001) and Shariki (1994).

Copyright protects the expression of an idea and not the idea itself. If we assume that copyright will protect ideas, imagine a world having only Counter-Strike, PES and Shariki as a monopoly on games market with no alternatives to play. For Shariki to sue some of its idea followers, Bejeweled or Candy Crush should have copied some particular element of the game, such as some sound effect, figure or some parts of the code. This is the most easy and obvious kind of violation.

The international practice also enshrines the merger doctrine, under which the same expression of an idea is allowed, when there is intelligibly limited numbers or only one way to express the idea, hence they “merge.” A doctrine of “Scènes à faire” or “scenes that must be done” is also used in a lot of Commonwealth and some other states. Pursuant to this doctrine, some elements are necessary to follow from a common theme. For example, in Walker v. Time Life Films, US Court has stated that the scenery that would include drunks, stripped cars, prostitutes, and rats are inevitable in a film about cops in the South Bronx. To prove the violation in such cases is much heavier.

Case law

Let us analyze two similar cases, where Japanese Data East Corporation (further, the “DECO”) was on both sides of the lawsuits on the same issue. The first case was in 1988 when DECO sued Epyx for copyright infringement of their highly successful game “Karate Champ.” “World Karate Championship” made by Epyx, on the opinion of DECO was infringing their copyrights on “Karate Champ.”

From left to right gameplay of: Karate Champ (1984) and World Karate Championship (1985).

Despite the fact that both games had common 15 noteworthy features, the Court rejected the claim. The Court found that these elements were unprotected from the copyright perspective, as they referred to Karate as a martial art and were intangible from the sport itself. Hence, left without protected similarities and being unable or inapplicable to prove that those elements protected were copied left DECO with nothing. Respectively, in this case, the idea was the same; however, the expression was found not violating copyrights of DECO.

In 1994, DECO is on the adverse side of the lawsuit. it is being sued for copyright infringement by Capcom. Capcom has developed, and released Street Fighter II in 1991 and DECO has released Fighter’s Story in 1993, “inspired” by first as stated. Both games idea is that you need to reduce the opponent’s character health bar to zero by punching him with your character through special moves (something like Mortal Combat).

Once again the Court has upheld its position on the idea-expression, stating that fighting technics were intangible from the sport itself are public and not copyrightable; the characters and the background are stereotypical, enjoying protection under the doctrine of “scènes à faire”; the expression means were different. There is a presumption between legal professionals in this field, that infringement of copyrights is most likely to be proven through copying the characters. This is also found in case law. However, in this case, the Court has stated that it is a stereotype that “Japanese karate guy,” “Chinese kung-fu lady,” and “Angry blonde American martial arts master” are fighting in this genre, thus it falls within “scenes a faire”. The Court also noted that the defendant has been creating games of this genre for a while, as well as previous DECO case, where it was a claimant and lost. Call it karma!

Well, if after this you are dreaming of “borrowing” some classic stuff and getting rich just wait a minute. Everybody knows Tetris, right?

Take a guess

By any chance, we do not doubt your Tetris skills and knowledge, however, it took you a while to guess where it is (Tetris is left). Among others, this was the main Court argument in the case of Tetris v Mino (2012). In this case, the expression of an idea was copied till such extent, that it was hard for one to understand that it is not Tetris while playing Mino. Thus, violation of copyrights took place.

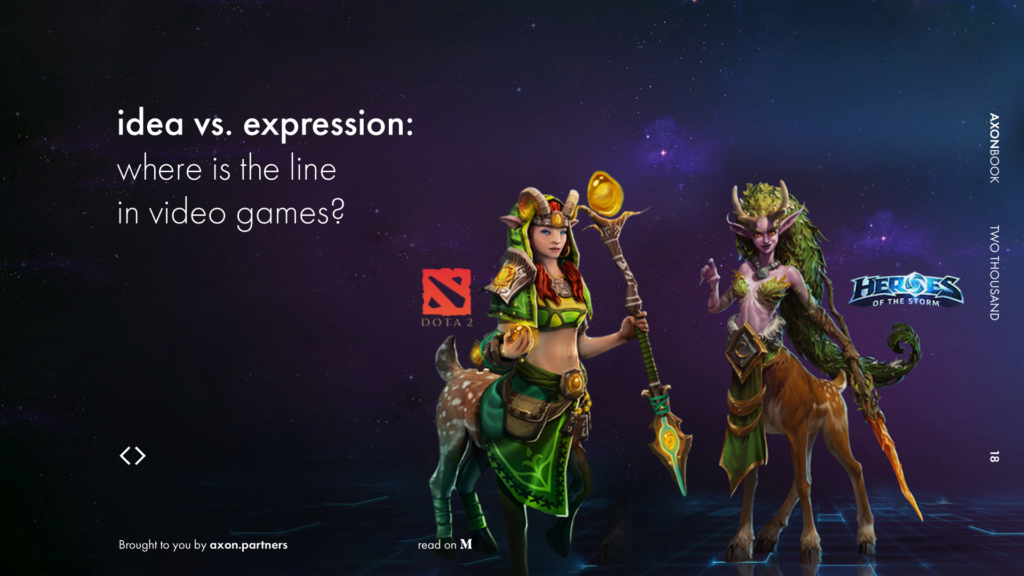

Ok, we were joking. Of course, you might try to “borrow” some idea and get rich, but first one landmark case should be settled to figure out till what extent is it applicable. In 2015, Blizzard filed a case against uCool and Lilth Gaming for infringement of copyrights. The case was based on copying of characters of Blizzard’s game “DOTA 2” by Lilth Gaming and uCool mobile games, respectfully “Dot Arena” (February 2014) and “Heroes Charge” (August 2014). Blizzard stated that almost every character was copied by them in two-dimensional version. Our good friend that plays DOTA for a long (not us) said, that they fully copied heroes, their descriptions, and abilities. That was found in the Blizzard argumentation as well.

From left to right: Enchantress from DOTA 2; Rynn the Chaplain from Heroes Charge; and Eva from Dot Arena.

Back in 2015, the Court has dismissed the claim with a “scènes à faire” argument, however leaving plaintiff space to amend its claim, which was done in 2016. The case is still in process and as judge Breyer stated: “Like Plaintiffs’ popular games, this copyright case has turned into quite the saga.” The epic part of the story is that Lilth Games sued uCool for copyright infringement and it was also declined. Prior Blizzard was in court with Valve concerning Dota rights, which was settled by a peace agreement. We hope this case will finally be decided on and be a landmark case, which is going to draw a precise line on idea vs. expression dichotomy.

Where is the line?

In cases where one can definitely state from his point of view that the games are just the same, the Court still looks from the idea/expression view and is more likely to determine “inspiration” rather than “copying.” As we can see, even if the elements are protected, they can be demolished of it, due to a merger and “scenes a faire” doctrines. In the same time, if the copying is not a result of artistic work, meaning where a game was copied to such an extent, that a player is in doubt whether this is an original game or not, the court without any doubts concludes on the violation (as in Tetris case). We think that DOTA 2 case will be a new era gaming IP landmark case, that will make some clearance on the idea/expression dichotomy. We mean, it is obvious that Lilth Gaming and uCool have stolen all of the characters!.

This Article was written especially for Yurydychna Gazeta by Bogdan Duchak and Artem Datochnyi.

Other post